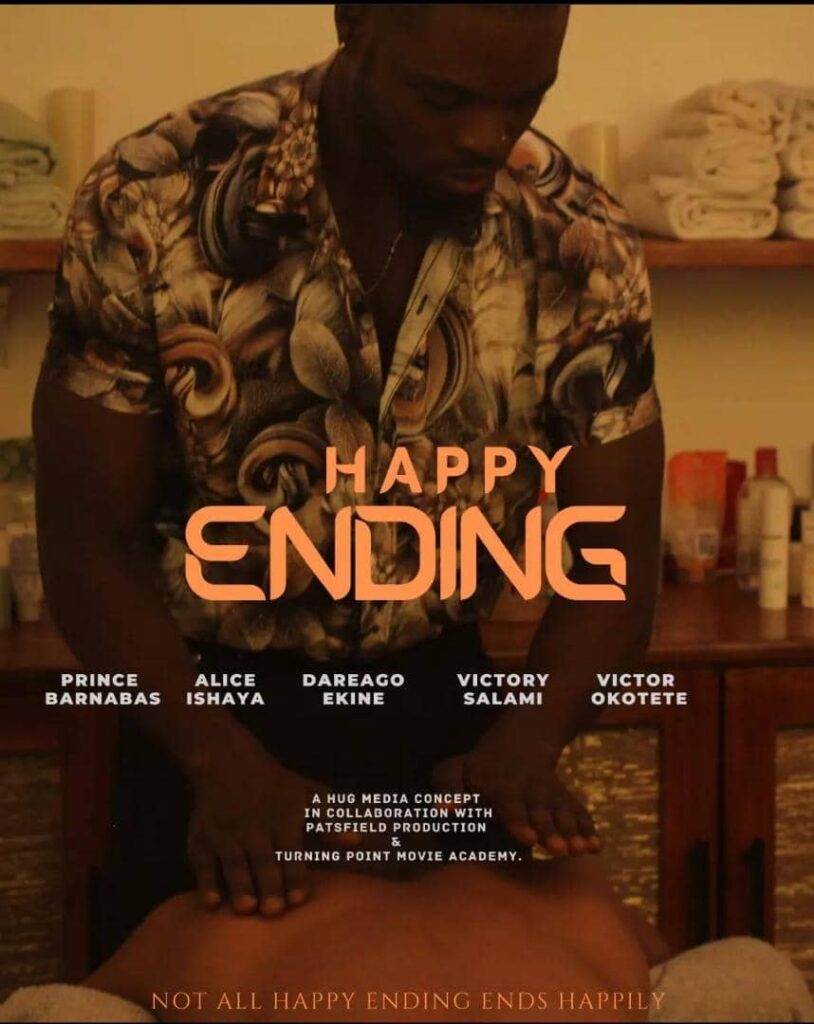

Happy Ending: A Compelling Case for Male Victims

“…a rape victim and a victim of a fatal accident were both gone forever. The difference was that the rape victim still had to go through the motions of being alive” – The Tenth Circle, Jodie Picoult. Cruel, inhumane and traumatizing are a few synonyms that attempt to capture the soul-destroying evils of sexual assault. Conversations touching the subject are as sensitive as it is harrowing for the survivors who still bear the burden of grief. Sadly, while incidences of female sexual assault plague societies of the world, male sexual assault is that poisonous undergrowth creeping unnoticed. “I’ve always seen filmmaking as a mode of advocacy for certain issues in the society. The idea behind the film as at when I started writing two years ago was me looking to talk about the ills in the massage profession but as time went on, the project took me through a walk and I arrived at male rape as a key subject matter”, Godwin Harrison, writer and director of Happy Ending tells Filmrats. Happy Ending narrates the ordeal of two rape survivors (a man and a lady) who venture into the massage profession only to encounter their perpetrators. The film paints a grim portrait of the unspoken trauma male rape survivors suffer as a consequence of society’s numbness towards the matter in question. Research affirms this growing negligence to be fueled by a state of unawareness that attributes no real danger to the sheer possibility of sexual assault on a male by a female or another male, and the reluctance of said survivors to report cases for fear of shame and infantilization of their status as men in the society. “Happy Ending was inspired by many true events. The idea came about from my desire to talk about male rape and how the society turns a blind eye to survivors of male rape. Being a rape survivor myself, molested at the age of 7 and 13, I know what it means to feel that painful restrain to reveal the truth to parents and friends and not seem like an alien. This experience inspired the project” says Harrison. On reasons why male rape incidences suffer a lack of due consideration, Harrison cites toxic masculinity as one that thumps the others. “In the society especially in the patriachial system, men are seen as super beings. Men are often seen as the perpetrators of evil and not victims. In the incidence of male rape perpetrated by women, people joke with the fact that the victim, at least, had an erection and must have enjoyed the act. And in cases where the perpetrator is a male, same people quickly discard the possibility of a man raping another man. This sweeping misconception is why we need more awareness, because for rape survivors, irrespective of gender, the moment the assault happens, you have no control over your being till the molester is finished and then you’re left to live a life of regret, isolation, bitterness and pain. It’s tougher for the men as it constrains many of them to die in silence from depression and suicide. A broken male soul does not speak. All they need is love and care until they are willing to speak” Starring Nollywood starlets Prince Barnabas and Alice Ishaya as leads, Happy Ending scored its first note of success at the 20th edition of the Accord Script Fest, winning the best script award. The project is helmed in production by HUG Media concept, Turning Point Movie Academy and Patsfield Production, and with an expected release in major streaming platforms after a proposed private screening with the ministry of Health and Youths, Kenya, Harrison hopes his film does justice at sensitizing the society on the existence and ills of male sexual assault. David Osaireme