KING OF BOYS: THE RETURN OF THE KING, EPISODE 4 “THE DEVIL’S REVENGE” REVIEW

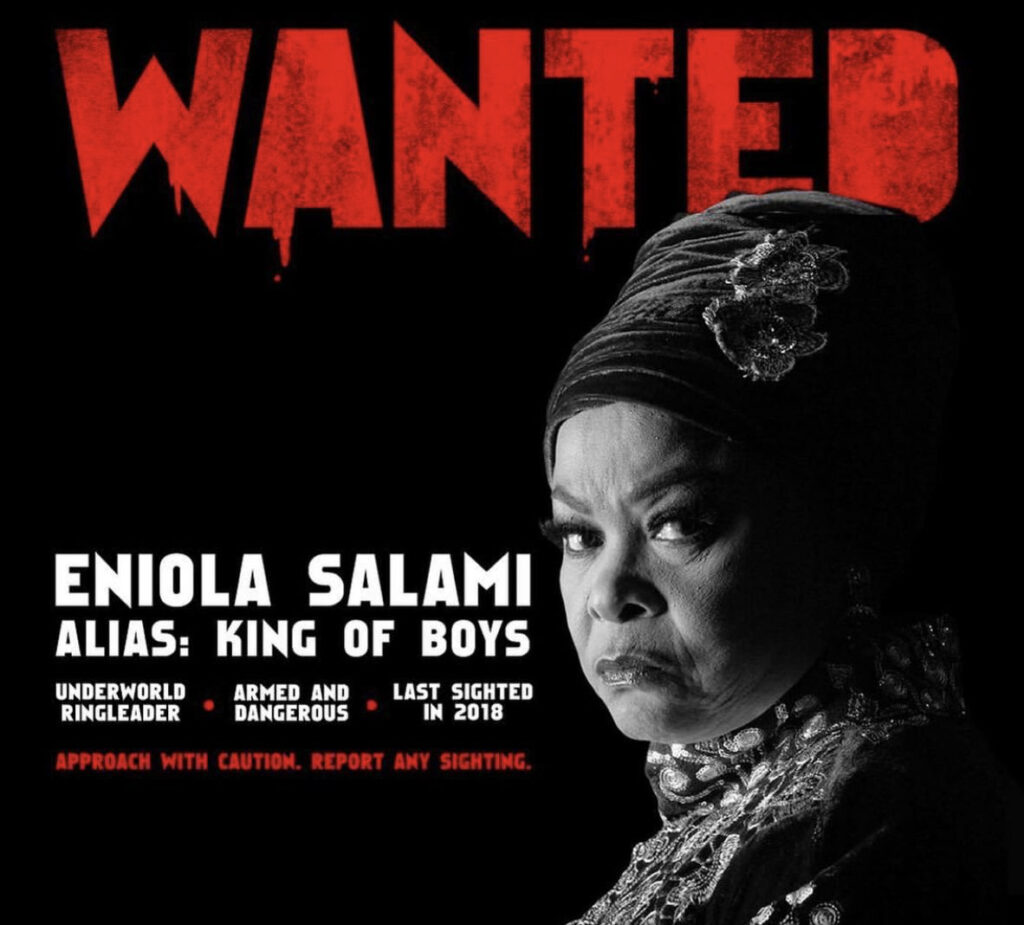

by Mr. X One of the earliest teasers of the KOB sequel touts Makanaki’s return from the dead as a major high point. Upon release, the audience, I presume, with piqued interests, skipped to this episode after the long-awaited Makanaki makes his first appearance in the final beats of the preceding episode. Setting the stage for an upsurge of events, the burst of verve and pace the show desperately needs as a soothing distraction from the proverb-laden dialogue and slow-burning heat of the gubernatorial elections. 5 years after the pulsating rumors of his death, the die-hard Makanaki, played memorably by Reminisce, makes his grand comeback pining for his pound of flesh. “Call this my resurrection” mouths the aggrieved soldier, with the deceptive poise of an apex predator, as he entertains the pleas from the goons of Odogwu Malay (his sworn enemy) who were involved in his murder. Here, Makanaki uncharacteristically favors a game over a massacre. The game? ‘Spin the bottle’. Only this time, the goons, guilty of disloyalty, are fated to death regardless of the outcome. Makanaki’s return doesn’t leap off as grand enough, for a man who’s made a miraculous resurgence after supposedly getting burnt to death. However, as the episode unwraps its folds, befuddling questions, deserving of answers, start to brew. For one, what’s the motivation for that two young boys that go wandering in the thick of the night in search of a dog, and mistake gunshot sounds as invitations to witness the killing of Malay’s boys? Despite its loose-fitting addition to the episode, one of the young boys does fulfil a purpose integral to plot progression. He informs Odogwu Malay about the ghastly occurrence that saw his goons maimed to death. Via a whisper from the shriveled boy, forced out by his wailing mother, Odogwu Malay discovers the perpetrator to be Makanaki, a name that stretches his face into shock. At the campaign front, Eniola Salami experiences splinters of success. No less than she expects after winning a close-door negotiation battle with the President (a point I’ll address shortly). At a press conference, Eniola is announced as the flagbearer of the selfsame party housing the President, to the roving applauds of her supporters. Here, Eniola starts to revel in the bliss of actually winning. With the precipice of power within hairsbreadth, she can almost reach out and touch it. The last card, or the penultimate card, has been flipped. The toils, sacrifices and torments start to pay off. She desires to rule, not with the rod of the provocative and adamant negligence famous among political leaders, but with the staff of protection, care and motherhood. A virtue she strives hard to preserve regardless of her acerbic inclinations. The prying reporter, Dapo, soon breaks the fanfare with damning questions (a poorly contrived approach by the way) directed at Eniola Salami herself. Noteworthy is, “Why do they call you the King of Boys?”, and somehow, Eniola Salami denies knowledge of the name, as expected, and breaks into humane consolations and touching anecdotes about her humble beginnings and philanthropy, sinking Dapo into the background, lost in the cheerful applauds of Eniola Salami’s avid supporters. This scene stands out as one out of many questionable instances where Eniola’s unslakable power over anything and anyone shines, save for the aggressive apparition of her younger self that haunts her thoughts now and then. While I commend showrunner Kemi Adetiba for her endeavor at delivering a project of this scale and, of course, her astounding production values, I find a bit of the grand narrative of the sequel a tad unsettling —the diminutive portrayal of the political offices and the key personnel that helm the affairs. Here, I speak of the hallowed office of the President as I promised earlier. Whether due to improper planning or incoherent research, some oversights, regardless, are rather unforgiving, especially when it concerns key details that define the Nigerian integrity and public image. Certain intricate details are better left unmentioned than misinterpreted. In this case, the inglorious representation of the President of Nigeria (played by Keppy Ekpeyong), the underwhelming depiction and the smallness of scope Kemi employs. This I first noticed in the preceding episode. My eyes bled through scenes where the office of the President of Nigeria is ill-treated as commonplace. A friend of mine believes Governor Randle possesses more charm and poise of the President than the President himself. One might argue that we never see the President outside his office or bedroom to judge, say, the strength of his security detail. The ease of access, however, in his featured scenes does so little to elevate his importance as the President. There are layers to politics, more so, Nigerian politics. How Eniola bursts through these layers, boasting a firm grip on negotiation and compromise from the dark corners of the underworld to the glorious seat of the Head of State is rather far-reaching and defeats the trueness of her external struggles. Her seeming control over everyone, including the President (who she casually regards in the press conference), fires her into realms beyond the normal. Who really is Eniola Salami? A metaphorical emblem of the unseen powers that be? Or just a returning political fugitive gifted so much power to clamp down on her enemies. Is Nigeria governed by the muscle of thuggery and not the prudence of policies nor the constitutional authority of the ruling bodies? A global spectator asks. Whether we choose to accept it or not, films create a powerful force of perception. Nigeria pales in comparison to certain countries with sinkholes in their governance but, through film and new media, said countries manage to influence and shape the public image of their governmental politics. This practice has guided many nations of the world: in America, in the Middle East, in Asia etc. Hence, there are existing films that spotlight the political space of countries and, if story-wise, the office of the President is even subtly hinted, it is given its due