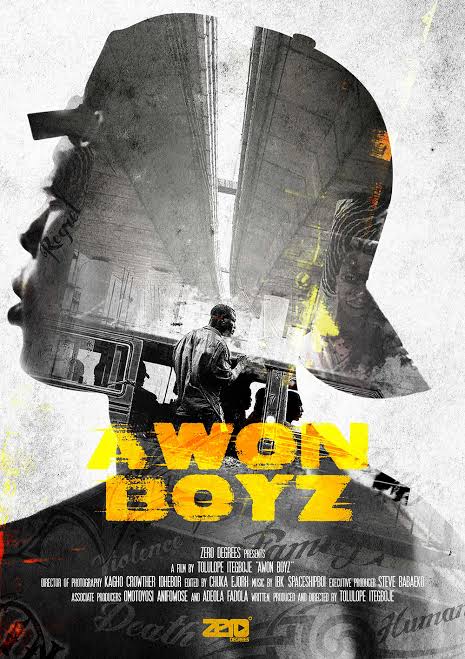

For many of us, we grew up seeing area boys on the streets and bus stops as we went to school, church, mosque, market or on long trips for visitations. We dreaded these guys because of their notoriety and because their actions mostly constituted a nuisance on the streets. Many times, their fights engulfed into large scale violence that led to loss of lives and properties. Our parents were quick to use them as references, telling us to face our studies squarely or we’d end up like “those boys on the streets”. Because, to them and by, transmission, us, the street is the den where dreams die. Later down the years, I found myself closer in proximity to some of these boys. While they hovered around, forcefully collecting money from motorists, I postulated and scratched my voice hoarse as a political pundit by newspaper stands. I was exposed to more redemptive sides of the boys. Beyond the raggedness and tendency for the excessive, they were there to help direct traffic, help motorists fix their cars and apprehend pickpockets or sexual harassers. This was new; it provided a counterbalance to previously held ideas about what these boys were all about. But I didn’t have a reason to properly reflect on the commonly misinterpreted significance of the boys until I watched the trailer of ‘Awon Boyz’ on Twitter. Curiosity pricked, I wanted more. But first, I must share an event that further pioneered the viewing of said documentary. I was returning from an event on a Friday evening when I witnessed a street fight between a couple of these boys around the popular Mokola bridge in Ibadan. I found my interest so piqued by the chaos that I did not even bother to run; instead, I decided to stay at a safe distance and watch. One of the watchers like me said, in English, ‘And these people might have parents, wives and children waiting for them at home’. Policemen were sitting a couple of meters away smiling and chatting away without making any attempt to stop the fight. It was the norm. Unexplained fights. Violence. The world is just fine. The fracas soon stopped, the writhing figure of one of the boys howling after receiving a Mike Tyson-esque uppercut to the jaw the departing image. My walk into the University of Ibadan, that evening, saw my mind plagued with questions. Not about the violence itself. But more contextual elements: Why are they on the streets? Do they love what they are doing? Are they not afraid of the dangers of what they do? Do they have families? These and more plagued my mind all through the next couple of days till I caught the documentary ‘Awon Boyz’ on Netflix. The documentary helped with my questions, gave insights into the lives of these area boys and helped in dispelling long term notions I’d formed about them. The story explores the lives of eight different boys who reside around Fela Kuti’s Afrika Shrine and Monkey Village, a slum known for its notoriety around Opebi. We use varying terminologies for these boys. Words like area boys, street touts, urchins, agberos, omo ita and so on come to mind. One of the interviewed boys is quick to rebuff the merit to the tag. This is a familiar disposition. One I probably hadn’t taken seriously until my viewing. Almost all the boys I have seen and interacted with on the streets don’t like to be called that name ‘area boys’. Most times, using the word ‘area boy’ represents an ill or an alien in the society and they don’t want to be associated with that. And I remember years ago that there was a time, one of the street boys in the newspaper stand I visited told a man never to call him an area boy again. It’s interesting how the documentary forced these memories out of the deep. I suppose that’s what relevant art does. It forces to a reckoning with self, leading to renewed examination of previously held biases. These boys believe they are human beings also who are just like everybody else searching for a means to make ends meet. Yes, the boys are rightly associated with hooliganism and banditry but there are back stories that explain (not justify) these tendencies. For many of them, the street is the only alternative where they can eke out means of survival. They make a living working as bus conductors, porters, car washers and so on while some go into pick pocketing and thievery. Some of them speak impeccable grammar, hinting at formal education, and I’m still forced to wonder the many possibilities if they had gotten opportunities. There’s the place for those who are where they are thanks to willfully made bad decisions. But investigations into both stories will reveal one underlying truth. The failure of the government. The realities of these boys are coloured by bad policies, poor policing, corruption, negligence and poverty. This should not just be a documentary to be kept in the archives but an opportunity for policy makers and the larger society to work towards providing opportunities for these boys. These boys are everywhere and will continue to increase in number if nothing done. There is a need for a concerted effort between thee state and federal government to empower these boys. The creative and sports industry is a sector many of these boys are willingly to thrive. The younger ones who are ready to go back to school should be encouraged to do so. For the entrepreneurial hopefuls, mentorship and grants should be provided. They are talented human beings whose potentials needs to be harnessed for the greater good. If they are left to continue to waste away, they will accrue in size and stature, becoming more lethal as societal menaces that even the government and citizenry will not be able to contain. There is still time for the government, corporations and well-meaning citizens to do something good before