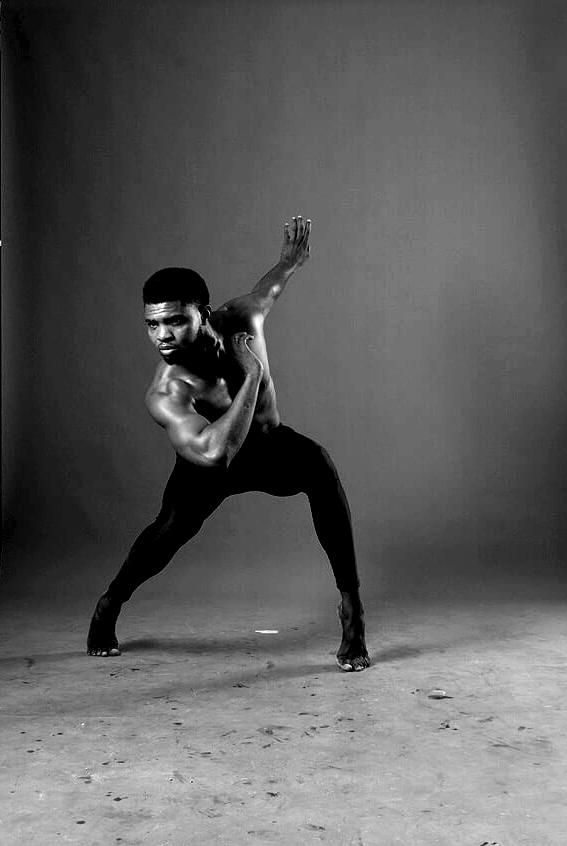

CHANGING LIVES: ONE DANCE AT A TIME

A woman of about 53 years saw one of my films sometime ago and started shedding tears. That is one of the best reaction and feedback I have gotten since my venture into film making. I hope to be able to create a virus in such a way that my film becomes a tool for total transformation of the human soul. Kenneth Agabata is a Dancer, Choreographer, Fitness Trainer & Filmmaker. Here he takes us through his idea of film and dance films in particular. He has made a couple of short dance films from Oblivion (2019) to Be Kind (2019) both of which are unique in the world they belong. FR: Tell us about your decision to venture into making films KA: My decision to venture into filmmaking reels from my passion for telling stories with dance. I’ve always believed that dance is a very powerful tool for telling stories, because before man had written language there has been body language and dance is probably one of the best forms of body language out there… in my opinion. So I figured that film making is actually a good way to visually tell my stories and reach out to the large audience that need to hear these stories, not forgetting the fact that I like to be different in everything I do. I decided that dance film hasn’t really been harnessed in Nigeria and therefore could be what sets me apart in the world of film making. FR: What would you like to achieve with your films? KA: I want to be able to tell stories that affect people’s lives, I want to be able to touch people’s lives with my film. A woman of about 53 years saw one of my films about somedays ago and she started shedding tears, that is one of the best reaction and feedbacks I have gotten since my venturing into film making. I hope to be able to create a virus in such a way that my film becomes a tool for total transformation in the society. “Oblivion is a dance film about a happy couple cut mid-air by the bloody band of herdsmen” FR FR: What are the challenges of making a dance film especially in an industry such as ours? KA: I feel one of it is financing. I am not like super rich, and I am just making films out of passion. So I think that affects everything since there is no commercial intent to it at the moment, so having to find like-minds that are ready to believe in your dreams at this moment and want to participate for almost free could prove challenging. Also the technicalities needed in achieving an almost perfect performance can be quite mind blowing, from getting an actor that can dedicate his time and effort towards interpreting a character and also dance well- sometimes it is about getting an actor that can dance or a dancer that can act- to creating a choreography and having it conform with the space available for action. A lot of things come into place, especially when a place is not available to rehearse the choreography before shoot or when you cannot lock down a street before the shoot, these could be quite challenging. And lastly, there is the problem of availability of personnel. Since they work on subsidized payment, getting them to honour your schedule can prove tasking, so basically it is the technicalities and finance. FR: What would you say is the future of dance films in Nigeria? KA: Well, the production of dance films in Nigeria especially as a measure for societal change hasn’t really been explored in Nigeria, one would wonder if it is due to the physical strain as much as the mental and financial, but seeing the growing interest in dance and having youths such as myself being interested in dance films, I believe that we can get to a point where this style will be shown regularly on our screens and Nigerians will want much more than the normal thereby making it well recongnized, and hopefully, we will get it right and have enough investors that believe in our work enough to drop the bills. FR: Tell us about your inspirations and mentors in Nigeria and why have you chosen them? KA: As weird as this might sound, my inspiration comes from God Almighty. I think I have a gift of seeing and feeling the things around me: people’s pain, people’s anger, the little mishaps in the society which others would see and probably pass over, but then to me it is these things, which I will term “the common” that build up materials for my thoughts and gives me the burning desire to go out and see what little change i can make when wielding my tool of dance, choreography and the process of filmmaking. In the process of doing this, I believe I am touching lives About my mentors: In dance, I have Chibuzoer Ikonta popularly known as Slim. He is the CEO Body Language. He has been a great “sensei” in molding my dance abilities and dance views. Apart from teaching me the dance styles, he has been like a big brother. He has helped keep the dance in me pure, real and not to derail. His passion and sense of direction, resilience has rubbed off on me and is a source that I can always go and tap from. For Film, I wouldn’t particularly say I have a mentor in Nigeria, but the one person I admire his works and thoughts is Solomon Essang, he is a Cinematographer and Director. I like him because I like his view about Filmmaking, his thoughts about the role of planning. He was actually the first person who gave me an insight on how to direct and shoot a dance movie, in terms of lighting, costuming, character development, colour choice, location choice and so on. FR: Which dance film do you