“He Who Shares Name With Yam” – The Tradox System – ‘Chukwu Martin

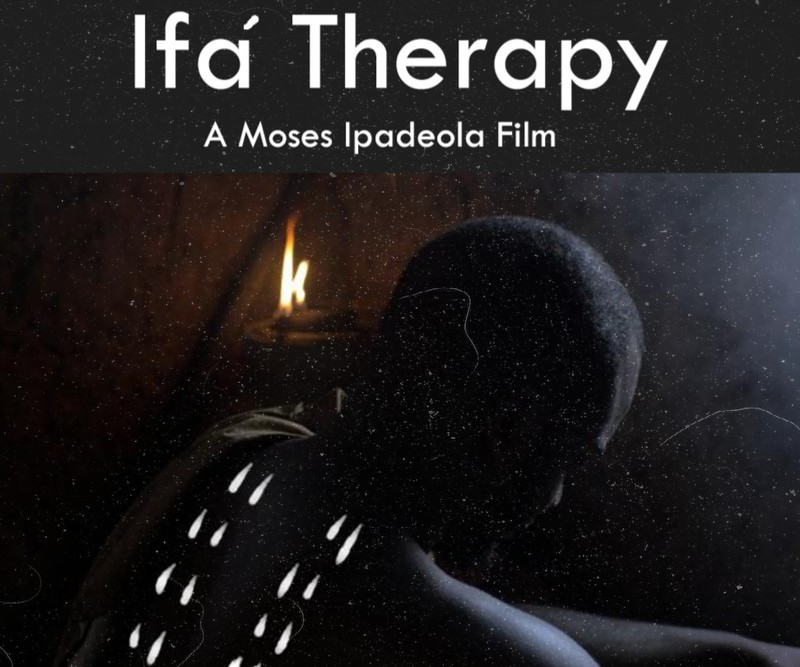

Ipadeola Moses’ Ifa therapy gives quite a lot to theatrics. He wants you to find the answers in the philological symbols and the metaphoric images he presents. Black – “After the departure of Orunmila (500B.C), Ile Ife was in tumult. The people appealed to him to return, he refused but gave them an oracle to be consulted whenever they needed his assistance. That consulting oracle is Ifa System…” – Sophie Bosede Oluwole “The Ifa system is still in use till today and has spread across the world. The Ifa literary corpus contains about 400,000 verses, which solves numerous life problems like health problems, witchcraft, and psychological problems.” We fade in to see Owu, 1920, in ruins. We slide through the broken potsherd and the wrinkled mud houses cut at lintel. With eagle eyes we capture three tiny human figures make their way through a snaking path guarded by bushes – the Ifa scholars (as credited). There’s an emergency. A young man, Akanni (TemiFosudo), has a Dane gun to his jaw, in view of taking his life. He’s plagued with making the choice between life and death. Like the opening images of the film, this man is broken. He’s neither dead nor alive; the Yoruba call this walaye bi eniti o si, often caused by a health challenge, or poverty. In this case it is the former. Akanni, we soon hear has just returned from war, and maybe has developed in the English verbiage – Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) which is agonizing to deal with on an individual and societal level. Akanni’s attempt to take his life would stem from the fact that this mental illness taints his family’s public image, as this has never been the case in his lineage. Hence, he is compelled take his own life. For it is especially within the construct of the Yoruba traditional belief system that Ikuyajuesin: “death is better than shame”. So he’s caught in that struggle between life and death. The struggle is visualized with voices and images offering him three suggestive tools for his suicide (a noose, machete, poison). The director attempts to make the journey quick but Akanni doesn’t look ready. A woman; his wife (Bisi Ariyo) who could be mistaken for his mother, intervenes and here the dialectics begin. In a recent interview with filmratsclub.com, the director notes “…I realized Orunmila had cured not just health problems, or financial problems but also psychological problems as well. In a period that came way before the advent of the Europeans “Therapy Sessions”. So the story of suicide and hereditary came to mind and I just wanted to show the world that before the advent of the popular therapy sessions, there was one that belonged to us here in Africa, in the Yoruba world.” The Cure is The Ifa Therapy The Three Ifa scholars arrive and begin their work, reciting some incantations, some Ifa verses and a eulogy. They call Akanni “IyeruOkin(can be translated as “one related to the peacock), descendant of Olofa Mojo, who Shares names with yam”; they discourage his suicidal motive and remind him that his lineage, the Ikoyi warriors, “don’t take arrows on the back. Whoever does so acts cowardly. Your forbears are known for taking arrows by the chest”. The three wise men emphasize ‘Patience’ through proverbs and story, they say Orunmila was the patient man who Olodumare (Supreme Being) bestowed with other gifts because he chose patience over all other things. “Patience is father to character” they said, he who has patience has it all. He enjoys long life, honour and every good thing life offers like honey. They tell him that the issue is not worth the mental stress, because Ori (the Yoruba concept of destiny) is the maker of one’s fortune. It is a therapy session with only the therapist speaking. They continue by saying “Patience will resolve the issue on ground” and constant prayer would help. They count seven cowries and hand them ceremoniously to Akanni. They exit chanting “Iwori Ibere, hang not, there’s plenty of goodness waiting ahead…There’s plenty of goodness coming behind” as husband and wife embrace in hope. They must be patient. The session comes an end. But how well does this session help the patient? How sufficient is the counseling in Ipadeola’sIfa Therapy? Therapy is the attempted remediation of a health problem, typically following a diagnosis. Treatment is determined by the agreed cause of mental illness by therapists. According to Orisa Lifestyle Online, mental health is determined in three ways: ‘Amutorunwa’, that which accompanies you from “heaven”, ‘Iran’ that which you inherit and ‘Afise’ that which is caused by affliction’. In Akanni’s case it is Afise, an affliction. The Ifa scholars don’t provide a diagnosis of which we were aware. They didn’t conclude that the effect of the war caused the mental illness or neither was it an ancestral ailment. The authority of the therapy on screen with Akanni seemed to climax quickly, we are left to assume that this therapy would continue in another time, possibly a gradual process that called for patience. But did it work? Fast forward to future 2018, Lagos. We see polished buildings and skyscrapers – unlike the debris of our opening scene, in long forgotten Owu. This is metropolitan Lagos. The framed picture of a Man and a Woman lean side by side on the wall in a two-bit one room apartment. On the bed is a military uniform and two books. We can pick out the word “Psychology” from the one with a blue cover, the other is a book by Stephen R. Covey titled “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People”. The man whose picture hangs on the wall sits at the reading table, getting drunk and toying with a gun. This scene is reminiscent of the previous scene with Akanni holding a gun to his jaw, immediately we sort the connection between these two characters. This man’s name is Akin, he’s in fact Akanni’s grandson. And like his grandfather,